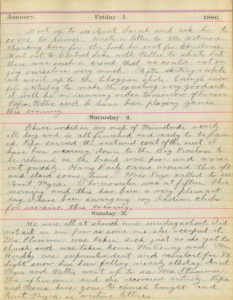

Notes written by Emily Dickinson, a WWII soldier’s letters home, Prince’s high school yearbook, and an 8mm film reel labeled “Gay Nineties Staff Party” were among the highlights of my tour of the Hennepin County Library’s Special Collection this week. Everyday artifacts tell rich stories about our past, and librarians are working hard to preserve today’s history for tomorrow’s generations. However, as our lives move online, there are fewer physical artifacts of our thoughts and experiences. What sort of story will this generation have, if our personal histories are easily deleted with a click of a button?

Personal effects have been a significant part of our historical record, adding insight to more public data like newspapers and government documents. While this generation will have no shortage of public records (what with Library of Congress archiving our tweets and the Internet Archive saving everything else), personal records of our lives have become far less tangible and typically more private.

Will texts to loved ones be passed down through generations? Will future historians have access to emails between world leaders? Do our password-protected notes and journals die with us? Just think about if Anne Frank had written her diary on a password-protected smartphone and her story had been lost forever.

Saving our digital possessions for future generations takes a lot more forethought – it’s a lot easier to find a departed loved one’s diary or box of photos, than it is a tumblr blog you didn’t know they had. It’s important not only for individuals to be deliberate about saving pieces of their digital lives, but public institutions should also be proactive in collecting and preserving these personal digital artifacts, just like they do now with books, letters, and other objects. If everyone submitted even one of their text or email conversation to the library, that would be a special collection indeed.